I am the last witness of time set on fire.

When my eyes burned I could finally see, with snow clarity, the great truth: I am not a piece of this puzzle by choice..

You fit in if you want.

Maybe the rest of the world is wrong and you don't know what to do with your reason..

So right.

Could be. everything can be, buddy.

Give me your hand,

give your cardboard crown and come with me. Even if it seems impossible, despite so much darkness, everything is light.

Everything is future in the kingdom of the helpless.

May the times continue to change. Above our heads the bluest sky in the world will continue to shine. A sky like always. That never changes.

Concerts / Recitals

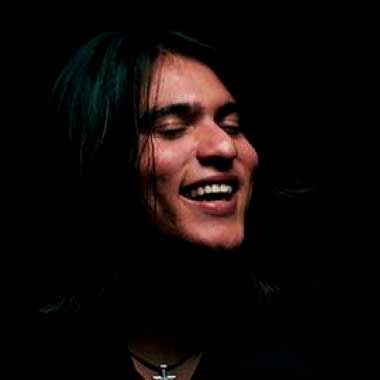

XXIII Flamenco Biennial. David Palomar

30/09/2024

@

23:00

25€

Sevilla

Sevilla Málaga

Málaga Jaen

Jaen Huelva

Huelva Granada

Granada Córdoba

Córdoba Cadiz

Cadiz Almeria

Almeria A tourist and cultural vision of flamenco

A tourist and cultural vision of flamenco The Guitar, last to join.

The Guitar, last to join. The history of flamenco with respect to its geographical distribution

The history of flamenco with respect to its geographical distribution The present and future of the genre. The Fourth Golden Key of Singing.

The present and future of the genre. The Fourth Golden Key of Singing. The festivals

The festivals Revaluation of flamenco. Third Golden Key of Singing

Revaluation of flamenco. Third Golden Key of Singing The Flamenco Opera

The Flamenco Opera Flamenco in Madrid. The Pavón Cup. Second Golden Key of Singing

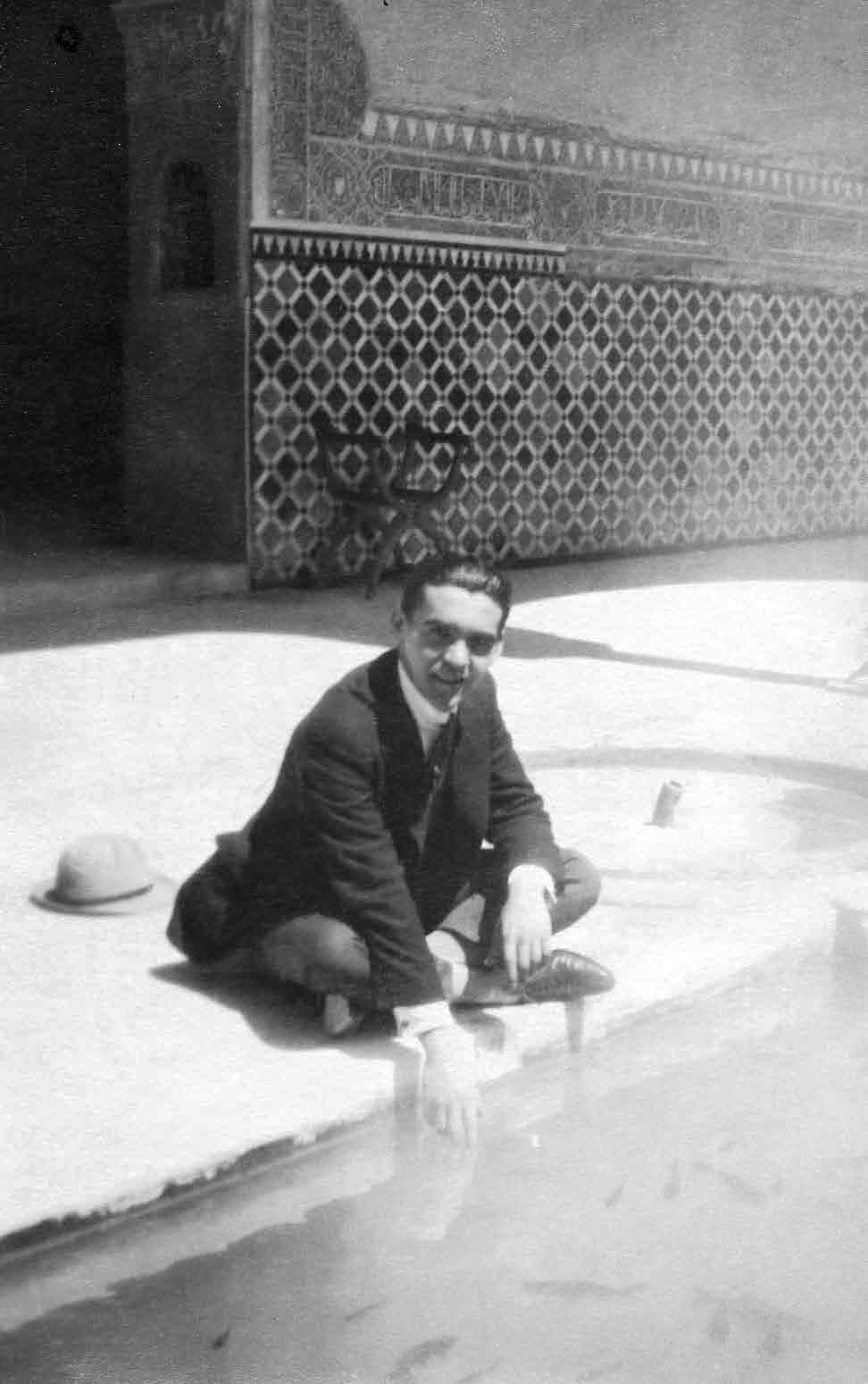

Flamenco in Madrid. The Pavón Cup. Second Golden Key of Singing The contest that took place in 1922 in Granada

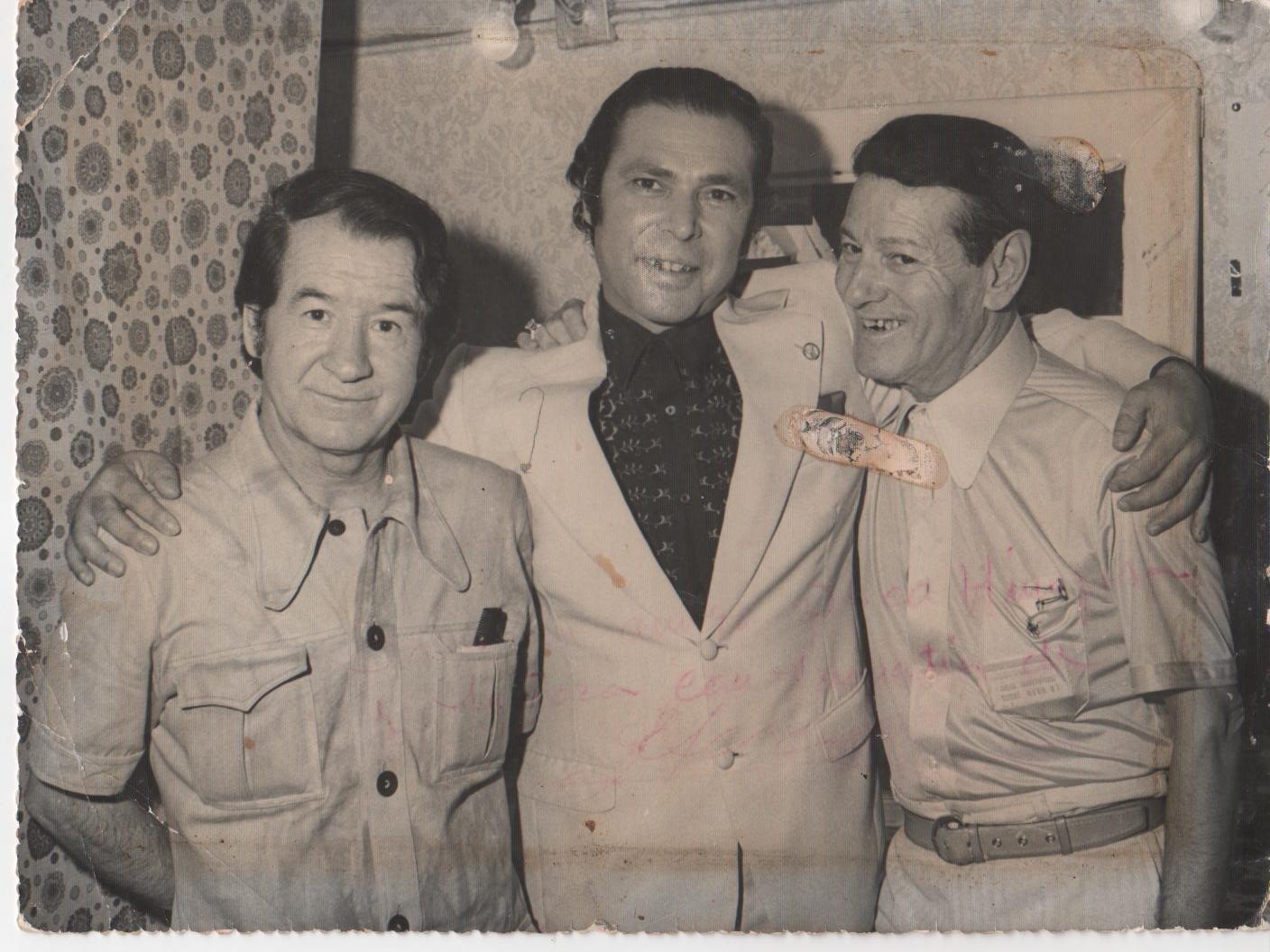

The contest that took place in 1922 in Granada The great creators. The Golden Age. The Singing Cafes

The great creators. The Golden Age. The Singing Cafes Evolution. Hermetic Stage. First singers

Evolution. Hermetic Stage. First singers Origin of the word “flamenco”

Origin of the word “flamenco” First written references

First written references Musical background

Musical background